No other kicking technique is as synonymous with modern martial arts as the Roundhouse Kick. At first glance, this technique might seem to have been a staple of martial arts for at least a hundred years in its current form, much like the straight punch. However, the history of the Roundhouse Kick includes surprising turns that are sure to intrigue modern practitioners.

Any fighter with an interest in kicking is naturally drawn to the Roundhouse Kick. Known by various names and applied across a wide range of styles and applications, listing all its names would be a considerable task.

The complete history of the Roundhouse Kick remains unknown. Unfortunately, like most martial arts techniques, it shares this obscurity. This ambiguity has led to disagreements among styles and philosophies within the modern martial arts community, sparking many debates over who “invented” certain techniques. Yet, if we look back, the Roundhouse Kick of the past differs significantly from the one we see today.

The modern Roundhouse Kick has multiple forms, generally falling into two categories: the Short Roundhouse Kick and the Long Roundhouse Kick. These categories are distinguished by how the hip is utilized during the kick’s execution. This distinction can be confusing for practitioners who lack the experience to differentiate between the two. Simply put, the Long and Short Roundhouse Kicks differ in range and, according to some, in power generation.

Long Roundhouse

If we examine Figure 1 from 1973, we can observe notable differences between the traditional and modern Roundhouse Kick. In this image, a Karateka performs a Roundhouse Kick using the instep as the striking surface. The hips are turned, with one hip pointed toward the target and the opposite hip away—a movement somewhat consistent with the modern Long Roundhouse Kick. However, the upper body positioning is markedly different.

Book, 1973, This is Karate, by Masutatsu Oyama

In the image, the Karateka’s upper body twists relative to the hips, as if he is looking “around” his striking leg. This same phenomenon was common among Taekwondo practitioners of the era, with the chest facing the target. In contrast, during a modern Long Roundhouse Kick, the upper body generally stays “behind” the striking leg when viewed from a similar angle. This difference has made the Long Roundhouse Kick a staple technique among fighters who emphasize kicking and targeting high.

Consider a contemporary example of the Long Roundhouse Kick. In Figure 2, a Tireur performs a Long Roundhouse Kick, with the upper torso aligned with the hips and no upper-body twist. The Tireur is positioned behind the striking leg. However, one key aspect to note is the heel of the supporting leg.

Osvaldo george, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

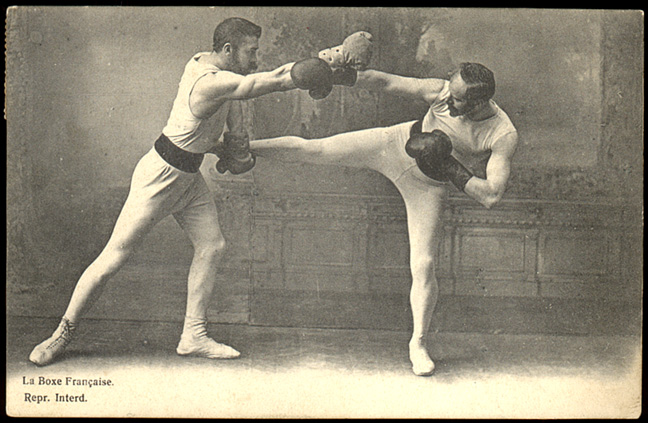

When we examine the supporting leg, we see the heel turned as far as possible toward the target. If it turned any further, the Tireur would risk injury or lose balance. This heel positioning is common across styles for the Long Roundhouse Kick. Was the Tireur’s style, Savate, an outlier? Looking at an older example, we see similar positioning as the Karateka’s Roundhouse Kick. Figure 3 shows an earlier example, with the Tireur’s upper body twisted, likely staged. Here, the Tireur blocks his opponent’s reaching arm while his striking foot is trapped, suggesting the upper body twist might aid in simultaneous blocking. This form aligns with Figure 1.

Carte postale, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

A critical aspect across these examples is the supporting leg position in Figure 2, with the heel turned maximally toward the target. When did this change occur, and why? It’s difficult to determine. This evolution appears to have occurred across many styles, but the reason remains unclear.

The Long Roundhouse Kick is about reach, hence the term “Long.” When the supporting leg’s heel points toward the target (as seen in Figure 2), it allows the kicker to extend their reach. This is achieved as the body rotates on the ball of the supporting foot, moving the heel from one side of the toes to the other, propelling the kicker forward. While this distance is minor, it is significant. Less skilled practitioners often place their striking foot on the ground too close to their opponent after completing the kick due to this forward momentum. With practice, however, they gain control over their placement, eliminating this error.

The Long Roundhouse Kick is primarily used to target high areas, such as an opponent’s head. Reaching higher targets is challenging due to the need to maintain contact while raising the leg. To illustrate, if you stand with your arm fully extended against a wall and raise it, you must move closer to maintain contact. The same principle applies to your leg in a Roundhouse Kick.

Balance becomes crucial when aiming high. The higher you kick, the harder it is to maintain balance, as weight shifts significantly with the body supported on one leg. Pointing the heel of the supporting leg enhances balance by acting as a stabilizing foundation. Highly skilled kickers execute this motion seamlessly to prevent falling. Once mastered, the Long Roundhouse Kick also allows for increased power, better ability to overcome obstructions, and a reduced risk of self-injury.

Power generation is crucial for any martial artist. Many believe the Long Roundhouse Kick delivers more power than the Short Roundhouse Kick due to its mechanics. The rotation of the supporting leg, with its heel pointed toward the target, allows the entire body to contribute force to the kick. This movement is driven by the hips, which initiate the rotation and amplify power. Taekwondo practitioners often emphasize “opening up the hips” for this reason.

Leg movement and hip positioning are closely interlinked. Proper rotation of the supporting leg “opens up the hips,” enabling more powerful kicks. Simply put, the hips must move before the striking leg and require a clear path, which is why the rotation of the supporting leg is essential. While strength and body weight contribute, proper mechanics are crucial for a strike to achieve effective penetration. It’s the difference between merely throwing a rock and utilizing a slingshot—where the hip movement acts as the slingshot.

To better understand the hip’s role in power generation, try this experiment: Stand sideways about 6 to 8 inches away from a padded wall and slam your shoulder into it while keeping your feet grounded. Then, repeat the motion using your hip instead of your shoulder. Observe the significant difference in force.

The Long Roundhouse Kick also provides an advantage in overcoming obstructions, such as an opponent’s blocks or evasive movements. When targeting the head, the foot must navigate around obstacles to reach its target. The Long Roundhouse Kick’s more horizontal trajectory enables it to bypass these obstructions effectively.

One of the greatest advantages of the Long Roundhouse Kick is its reduced risk of injury to the kicker’s legs. Kicking can be risky, and experienced Taekwondo practitioners often recount injuries sustained from striking an opponent’s elbows. The Long Roundhouse Kick’s horizontal trajectory minimizes the likelihood of contact with elbows, thereby reducing this risk. While not entirely foolproof, the chance of injury is significantly lower.

Short Roundhouse

The history of the Short Roundhouse Kick is even more elusive than that of the Long Roundhouse Kick. However, the Short Roundhouse Kick may be more commonly used than its longer counterpart, which makes sense for several reasons. It appears to be the preferred kick among Kickboxers, Muay Thai fighters, and practitioners of other combat sports that emphasize targeting an opponent’s legs. The Short Roundhouse Kick excels in fulfilling this purpose.

Although the history of the Short Roundhouse Kick is unknown, substantial evidence suggests it emerged first. Reflecting on the earlier analysis of the Long Roundhouse Kick, it is reasonable to infer that the Short Roundhouse Kick evolved as a simpler, more direct technique, likely originating from the foundational mechanics of the Front Kick. The Front Kick, one of the earliest and most straightforward kicks in martial arts, likely transitioned from a straightforward motion to a slightly angled, rotational one, aligning with the natural progression of simpler techniques evolving into more complex variations. Further evidence for this sequence can be found in classical forms: while the Roundhouse Kick is notably absent, the Front Kick appears consistently, supporting the idea that the Front Kick preceded the Short Roundhouse Kick, which in turn preceded its longer variation.

B20180, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

The defining characteristic of the Short Roundhouse Kick is the limited rotation of the supporting leg. As a result, the supporting heel does not point toward the intended target, as it does with the Long Roundhouse Kick. This difference causes the striking leg to travel along a more vertical path. The orientation of the supporting foot can vary, with the toes pointing directly at the target or angled slightly away, but it does not achieve the full rotation seen in the Long Roundhouse Kick. Figure 4 illustrates the angle used on striking pads during training to accommodate the vertical path of the Short Roundhouse Kick. For comparison, Figure 5 shows the angle required for the horizontal path of the Long Roundhouse Kick. The Short Roundhouse Kick has both positive and negative outcomes for a kicker, affecting speed, power generation, potential damage to the kicker, and range.

English: Brandon L. Saunders, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Speed is the cornerstone of the Short Roundhouse Kick. Its mechanical chain is shorter than that of the Long Roundhouse Kick. Although, in theory, the leg moves at the same speed in both kicks, the Short Roundhouse Kick covers a shorter distance due to its more compact mechanical chain. This creates the perception of greater speed, though it is primarily a matter of distance traveled. Nonetheless, the shorter path enables the kick to reach its target faster, making the Short Roundhouse Kick an attractive and effective technique.

Power generation in the Short Roundhouse Kick differs significantly from that of the Long Roundhouse Kick. The Short Roundhouse Kick relies more heavily on the strength of the kicker’s leg alone, akin to the motion of kicking a soccer ball. While some hip movement is involved, it is significantly reduced compared to the Long Roundhouse Kick. This limited hip engagement makes the effectiveness of the Short Roundhouse Kick more debatable, especially when targeting areas above an opponent’s chest.

The greatest downside of the Short Roundhouse Kick is the potential for injury to the kicker. The vertical path of the Short Roundhouse Kick makes it challenging to bypass obstacles posed by an opponent, particularly the opponent’s elbows. Because of this vertical motion, striking an opponent’s elbow can easily result in debilitating injuries for the kicker. Consequently, the Short Roundhouse Kick becomes a high-risk technique when targeting areas at or above the level of the elbows.

Compared to the Long Roundhouse Kick, the Short Roundhouse Kick has a shorter range. Without a substantial pivot of the supporting foot or significant forward movement of the hip, the Short Roundhouse Kick lacks the reach of its longer counterpart. However, this limitation makes the Short Roundhouse Kick particularly effective at closer distances.

Somewhere in Between Short and Long

In the end, which kick should be used—the Short or Long Roundhouse Kick? Since the distance between the kicker and the target constantly changes, both the Short and Long Roundhouse Kicks are essential tools. Each kick serves a specific purpose depending on range, allowing the kicker to adapt effectively to the shifting dynamics of a fight.

Consider a straightforward example to illustrate the importance of range. If the kicker is close enough to strike an opponent’s hip with a Short Roundhouse Kick, attempting to kick the opponent’s head from the same distance would require a Long Roundhouse Kick, as the Short Roundhouse Kick would fall short. While this is a simple example, the necessity of both kicks becomes even more evident when varying kicking ranges are introduced.

What the future holds for the Roundhouse Kick is unknown. The evolution of this kick seems to have peaked in the 20th century. Now, well into the 21st century, it remains unchanged. The Roundhouse Kick continues to be a dominant striking technique among kickers, holding a position of prominence unmatched by any other kicking technique.

In conclusion, the Roundhouse Kick remains a cornerstone of modern martial arts, embodying both versatility and effectiveness. The contrasting mechanics of the Short and Long Roundhouse Kicks demonstrate the adaptability of this technique, allowing martial artists to respond to varying distances and scenarios with precision. While the Short Roundhouse excels in close-range combat with its speed and compact motion, the Long Roundhouse dominates at greater distances, leveraging power and reach. Despite its long history and established place in martial arts, the Roundhouse Kick continues to inspire and challenge practitioners, highlighting the timeless value of mastering foundational techniques. As martial arts evolve, the Roundhouse Kick stands as a testament to the enduring power of well-executed fundamentals.

Leave a comment